Do you really want more features—or, do you actually want to achieve objectives?

If we rephrase “requirements” as goals and objectives, we will see leaner, more nimble projects that move faster, cost less money and headspace, and lead to more impactful and successful outcomes.

Do you want “a website that does x, y, and z”—or, do you want “to launch an online store that has the best chance of growing into a successful business”?

When a client approaches their web designer or developer, it’s typically with a request for a piece of work. The request might be small (something is broken, perhaps) or extensive (an RFP)—or, somewhere in the middle in the form of a simple project brief.

At the lower, “something’s broken” end of the spectrum, requests are typically focused on a problem—leaving it up to the web designer to diagnose, prescribe, and implement a solution.

Project briefs and RFPs, on the other hand, tend to be focused on the solutions—the features and functionality the client believes they need. They are generally prescriptive—without much, if any, background on the objectives or goals—or even the “whys” behind the perceived needs.

We are expected to then provide a quote for the work based on lists of features and functionality—where we know what the website is expected to do but with little understanding of who it’s for, why they need it, or the underlying problems we are looking to solve. Not only do we not (yet) understand this but our clients don’t, typically, either.

It’s like approaching a builder and asking them to provide a quote for a house with x windows and y doors and all the other “features”—without any sense of who’s going to be living in it, what direction it will face, or what the land’s like that it will be built on. And, not only do we expect the builder to build it, we expect them to provide a quote before they’ve designed it.

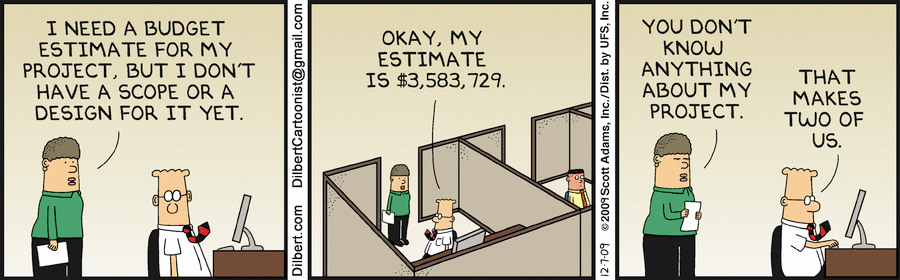

Dilbert put it so aptly back in 2009:

This is how the web design industry has been mostly operating. We have been building features and functionality; not researching, designing, and implanting solutions.

This is why I believe we have a complexity problem that is leading, in part, to slowing growth in the ecommerce industry.

As an industry, we have not only allowed this broken, backwards process, we have enabled it—because we have lacked the wisdom to realize what we’re doing and we have lacked the discipline to firmly guide our clients towards a better approach.

There is a better approach.

If you’re needing a website built, or features added, pause to think how you can reframe your needs. How can you communicate your goals and objectives so that your designer or developer can guide you better? Even simply adding the “why” to each request will have a tremendous impact on the potential success of the outcome—“I need this because I am experiencing x, y, and z”.

If you are a designer or developer or account manager or work with clients, how can you take the prescriptive request, briefs, and RFPs and reframe them to better guide your clients?

At Lucid, for instance, we will typically provide a quote for the audit and/or discovery phase of a project with an estimate for the design and implementation phases.

When we price a project, there are usually unknown unknowns. How can we be sure of how much work is required—or even if we are doing the appropriate work—if we haven’t done the research to reduce the unknown unknowns to known unknowns, so we are designing and building the best possible solution to a problem we fully understand?

What steps do we need to take to ensure “the tail isn’t wagging the dog” and we are leading our clients with experience, wisdom, and expertise?

If we rephrase “requirements” as goals and objectives, we will see leaner, more nimble projects that move faster, cost less money and headspace, and lead to more impactful and successful outcomes.